As featured in the Chemical Engineering magazine:

Bolted flanges on vessels, and their associated washers, are often seen as minor components in chemical processing facilities that may often be overlooked — until a critical problem arises. However, a closer examination of washer performance and design can help plants to significantly reduce maintenance time and costs, as well as improve operator safety. This article describes the real-world application of a new washer technology — the Velocity Washer — into a petrochemicals manufacturing plant.

The patented Velocity Washer (Figure 1) was developed to facilitate faster breakout times on critical flanges. Used on high-pressure, high-temperature industrial flanges in several industries, including petrochemicals, manufacturing and aerospace, the Velocity Washer reduces downtime and increases safety by eliminating galling, the primary source of seized fasteners.

FIGURE 1. The symmetrical design of these washers enables a simple installation in any orientation

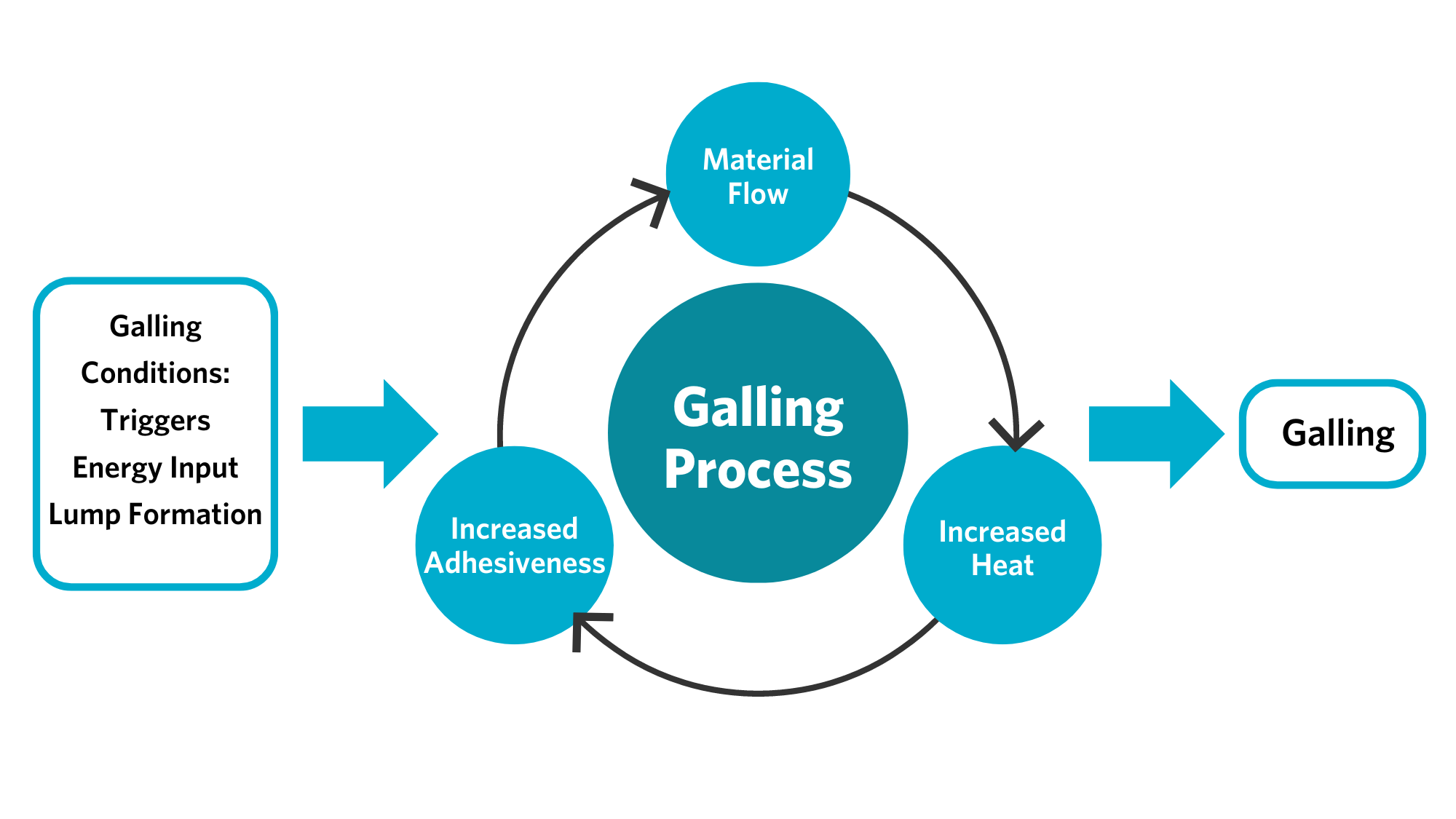

Galling occurs when metal parts are slid past each other under high loads. During motion, local stress, adhesion deformation and heat can drive the formation of metallic bonds until the two separate pieces of equipment become one solid piece. Galling is extremely common, causing costly delays and requiring dangerous extraction efforts in plants. The Velocity Washer eliminates galling by removing the load on a bolt before turning the nut. This results in faster and more predictable breakout times and the elimination of hot work, reducing labor costs and increasing worker safety.

A new approach to washers

The Velocity Washer was recently introduced for a multinational petrochemical corporation to address issues related to galled or seized studs and nuts, production delays and hot work in a process area. The work site washes out three large fluidized-bed reactors every nine months to clear solids buildup. The site had a long history of costly delays and potentially hazardous remedies when trying to unbolt the minicones on the bottom of the reactors to perform said washouts. Prior to introducing Velocity Washers, removal of galled fasteners required torching off the nuts, which added 4–5 h to the washout procedure and involved the use of an open flame in a confined process area. This practice also introduced integrity concerns due to the presence of high temperatures close to the sealing surface of the flange.

The obvious safety issues, high cost and repeated production delays prompted the site to seek alternative solutions. Hydraulic torque tools were proposed, but when used, they were unable to break the galled nuts. This is because the phenomenon of galling is much more complex than simple high friction — it is a fusion of the two parts at a molecular level. High-temperature bolt lubricant also failed to reduce galling as it baked off at process temperatures. The senior maintenance team at the site also considered hydraulic nuts. However, consultation led integrity experts to suggest the Velocity Washer instead, due to its focus on galling, lower cost and simple installation.

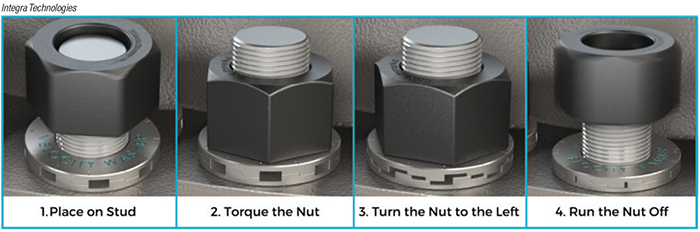

The Velocity Washer uses a crenelated design (meaning it has intrinsic openings built in) consisting of two stacked pieces that are installed like a regular washer. Due to their symmetric design, they cannot be installed in the wrong direction. The nut is torqued into place using standard procedures, and the Velocity Washer remains in place throughout operation. At breakout, the nut is turned 12 deg to the left. The Velocity Washer pieces collapse, removing all load from the nut and preventing galling before it can start. The nut is then removed easily. Figure 2 illustrates these steps.

FIGURE 2. The setup procedure of these washers eliminates the risk of galling

The petrochemical site’s engineers placed the Velocity Washer on one minicone-shaped flange to test effectiveness. At washout, total breakout time was reduced to just over one hour, compared to as much as five hours previously.

All galling — and consequently all hot work — was eliminated. Following this favorable outcome, the site’s maintenance team then installed the Velocity Washer on all minicone flanges. They also plan to install the Velocity Washer on other critical flanges as outages occur.

“We were skeptical that these would work because we weren’t sure that galling was the issue. It felt like the nuts never moved 12 deg, but locked up immediately. We trialed them on the reactor, which for some reason, had the most issues. They worked great. We were able to break all the nuts without galling,” explains one of the site’s maintenance engineers.